- Nick Water DR

- Published

- Updated January 12, 2026

- Articles

What is causing contamination of our drinking water in the UK?

Nick at the Water Dr is investigating water contamination in the UK. We'll cover key sources, risks, and how it impacts public health.

Across the UK the relentless production of wastewater from homes, industry, farms, urban runoff and ageing sewer systems has become a major and growing threat to rivers, ecosystems and drinking water sources. As pressures from population growth, climate change and modern chemical use increase, the limits of these systems are becoming harder to ignore raising urgent questions about how safely our water cycle is being managed.

Recent data shows millions of hours of untreated sewage discharges, rising pollution incidents and persistent chemicals like PFAS reaching rivers and estuaries even in protected areas. This isn’t theoretical: it’s happening now, and the examples below bring the issue into stark reality .Many emerging contaminants are small, highly soluble and resistant to both wastewater and drinking water treatment, allowing them to pass through treatment systems and migrate long distances. Below is a closer look at the main sources .

Domestic wastewater and sewer overflows CSO’s

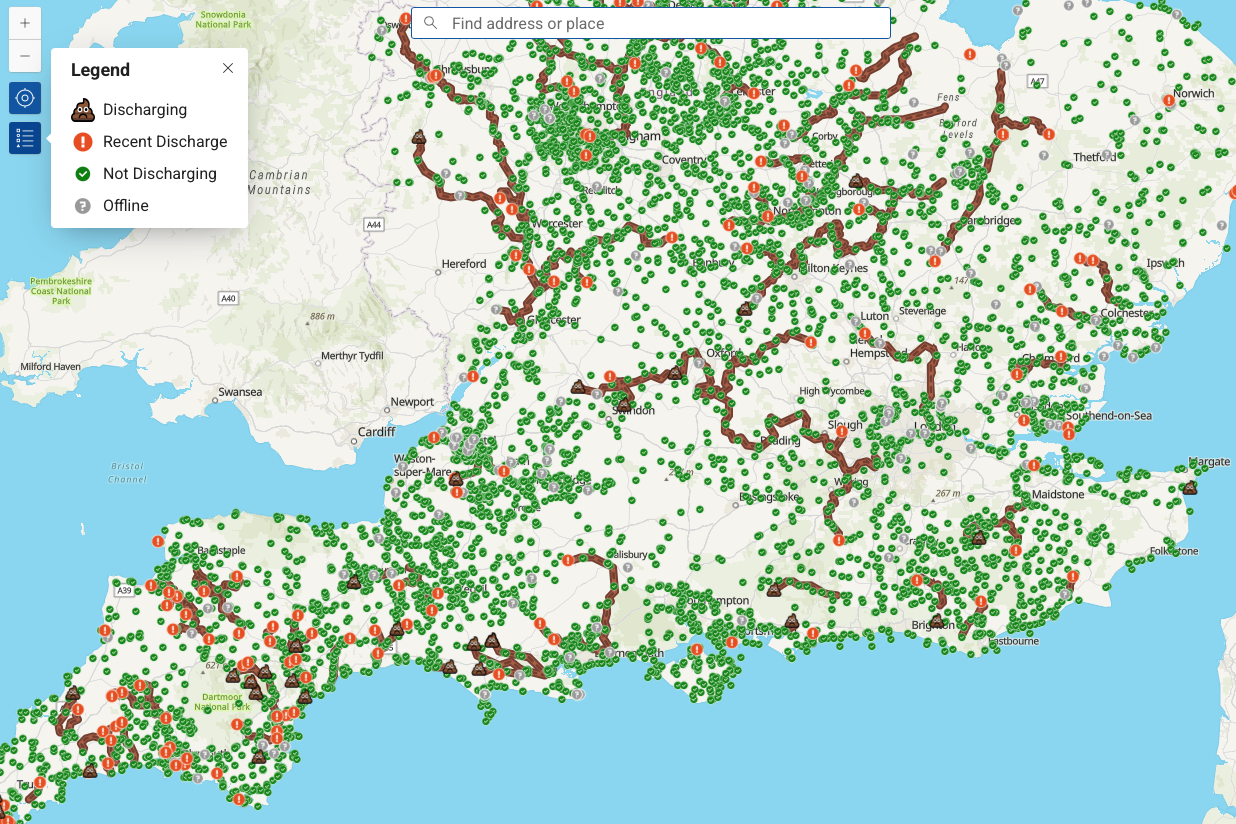

Everyday wastewater from toilets, showers, dishwashers, and washing machines is collected from homes across the UK and treated at wastewater plants, which remove solids and reduce organic pollution but do not make water safe to drink. During heavy rainfall, untreated sewage can still enter waterways via over 100,000 km of combined sewer systems , where rainwater and wastewater share pipes.

Originally designed for rare extreme events, these overflows now happen almost weekly, releasing raw sewage mixed with stormwater directly into rivers and coastal waters. Such discharges carry pathogenic bacteria like E. coli, nutrients that fuel algal blooms, pharmaceuticals, personal care products, microplastics, oils, metals, and household chemicals, creating sudden spikes in contamination that can overwhelm ecosystems, restrict recreation, and threaten downstream drinking water.

Historically, wastewater testing has largely been done by water companies, raising concerns about independence, but recent government action aims to strengthen monitoring. With aging infrastructure and more intense rainfall from climate change, combined sewer overflows represent one of the most acute and growing pollution risks to our UK coastal waters .

Take a look at your local area before you go for a dip !

Industrial Wastewater:

Many industries in the UK generate wastewater that can contain a wide and evolving range of pollutants, making it fundamentally different from domestic sewage and a significant risk to rivers and drinking water sources.

Even where regulation applies, industrial effluent may include heavy metals such as lead, mercury and cadmium, organic solvents and petroleum residues, toxic manufacturing by-products, and persistent synthetic chemicals such as PFAS, many of which are recognised as emerging contaminants of concern.

Because of this variability and toxicity, most industrial wastewater must undergo on-site pre-treatment, including pH neutralisation, oil and solids removal, chemical precipitation to strip out metals, or filtration and adsorption to reduce hazardous compounds. After pre-treatment, effluent may be discharged directly to rivers under bespoke Environment Agency permits or sent to the public sewer under a trade effluent consent, where it mixes with domestic wastewater.

The key risks arise when pre-treatment is inadequate or monitoring is limited: toxic substances can damage biological treatment processes, high-strength wastes can overwhelm sewage works, and persistent contaminants such as PFAS and certain metals can pass through treatment largely unchanged, accumulating in river sediments, sludge and groundwater.

Many of these emerging pollutants are not routinely monitored, meaning they can legally enter the water environment and increase the treatment burden for downstream drinking water supplies.

There are many UK Case Studies raised in parliment of Freshwater and Marine PFAS Contamination

Commercial Wastewater:

Hospitals, Offices and Retail SourcesCommercial wastewater in the UK, particularly from hospitals, healthcare facilities, offices, hotels and large retail sites, presents distinct contamination risks that are not fully addressed by current wastewater treatment and monitoring frameworks.

Healthcare-related effluent can contain antibiotics, pharmaceutical residues, disinfectant by-products, hormones, endocrine-disrupting compounds and specialised cleaning chemicals, all of which are increasingly recognised as emerging contaminants of concern. Unlike industrial discharges, commercial wastewater is usually treated as part of the domestic sewer system, with limited requirements for source-specific monitoring or pre-treatment.

At sewage treatment works it undergoes standard physical and biological treatment, but many of these substances are poorly removed, allowing low but continuous releases into rivers. Research and water quality monitoring indicate that antibiotics and disinfectants from hospitals can alter microbial communities downstream and contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance in the environment a risk that is rarely assessed in routine compliance testing.

Key gaps in the UK system include fragmented reporting, limited monitoring of pharmaceuticals and hormones, and regulations focused on traditional pollutants rather than biological or chemical persistence, meaning commercial wastewater remains a diffuse but growing threat to river health and downstream drinking water treatment.

Agricultural Wastewater:

Runoff, Nutrients and Sludge Agricultural wastewater is a major source of diffuse water contamination in the UK, affecting rivers, lakes and drinking water catchments through field runoff, livestock waste and the land application of treated sewage sludge (biosolids).

Runoff from fertilised fields and animal housing carries nitrates and phosphates, slurry, silage liquor, pesticides and herbicides directly into ditches and rivers, driving eutrophication and harmful algal blooms.

A high-profile example is Lough Neagh in Northern Ireland, which supplies around 40% of the region’s drinking water and has suffered severe cyanobacterial blooms linked largely to nutrient pollution from agriculture and sewage a pattern mirrored in many UK catchments.

A less visible but growing risk comes from the widespread use of sewage sludge on farmland about 3.5 million tonnes of sludge the solid waste produced from human sewage at treatment plants is put on fields every year as cheap fertiliser. Campaigners have long warned about a lack of regulation and that sludge could be contaminated with cancer-linked PFAS chemicals, microplastics, and other industrial pollutants with limited routine monitoring for these substances .

These pollutants can accumulate in soils, leach into groundwater and slowly enter rivers over time. Key gaps in the UK system include weak controls on diffuse runoff, limited tracking of sludge-borne contaminants and regulations focused on nutrients rather than long-term chemical persistence, making agriculture a chronic and hard-to-manage threat to water quality and downstream drinking water treatment.

Leachates: Hidden Chemical Pathways From Landfills

Landfill leachate ie the liquid formed as rainwater percolates through buried waste represents a largely hidden but scientifically well-established pathway for long-term water contamination in the UK.

Leachate can contain persistent and mobile pollutants, including PFAS and other synthetic chemicals, heavy metals such as lead and arsenic, and legacy toxins like PCBs and dioxins, many of which are resistant to degradation and difficult to remove once released. While modern landfills are engineered with liners and leachate collection systems, hundreds of historic and unlined or illegal landfill sites remain, often located near rivers, floodplains or coastal zones.

Investigations have shown these sites to be vulnerable to flooding, erosion and liner failure, allowing contaminants to migrate into soils, groundwater and adjacent surface waters. Because leachate pollution can be slow, diffuse and poorly monitored, it poses a chronic contamination risk that can persist for decades and create long-term pressures on drinking water sources and downstream treatment systems if not actively managed.

The subsequent emerging contaminants in UK Water

Conventional water and wastewater treatment in the UK is highly effective at removing solids, reducing organic pollution, and killing most pathogens, but it was never designed to eliminate the full spectrum of modern chemicals now entering the water cycle.

While standard processes can remove the majority of bacteria, sediments and some metals, many emerging contaminants including pharmaceuticals, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, PFAS, microplastics and industrial by-products are only partially removed or pass through treatment altogether. Even advanced technologies such as activated carbon, ozonation or membrane filtration vary widely in effectiveness depending on the compound, with removal rates ranging from under 50% to near-complete.

Thousands of chemicals detected in UK waters are not routinely monitored or regulated, including drug residues, hormone mimics, persistent industrial chemicals, transformation products formed during treatment, and genetic material linked to antimicrobial resistance. This growing gap between what treatment systems can remove and what modern society releases into water lies at the heart of the emerging contaminant challenge facing UK rivers, groundwater and drinking water supplies.

Pesticides such as metaldehyde, 2,4-D, clopyralid, and dicamba, along with metabolites from chlorothalonil, diuron, and flufenacet, are mobile and sometimes more toxic than their parent compounds, frequently appearing in groundwater near regulatory limits.

Pharmaceuticals and lifestyle chemicals, including antibiotics (ciprofloxacin), analgesics (paracetamol), caffeine, nicotine, and artificial sweeteners, enter water via excretion, improper disposal, and wastewater.

Personal care products (DEET, parabens, triclosan, UV filters, polycyclic musks) are biologically active, toxic, and poorly removed by treatment.

Industrial additives chlorinated solvents (PCE, TCE), flame retardants (PBDEs, TRCP), bisphenols, phthalates, surfactants (PFOS, nonyl-phenol), and some food additives pose endocrine, neurotoxic, and carcinogenic hazards.

Water treatment by-products such as trihalomethanes and NDMA, along with hormones, sterols, and ionic liquids, further complicate contamination.

Other frequently detected compounds include PFAS , polyaromatic hydrocarbons PAHs , triazine herbicides, bisphenol A, tributyl phosphate, caffeine, DEET, carbamazepine, triclosan, nicotine, and pesticide metabolites

UK Regulations: What Exists and Where Gaps Remain

The legally enforceable drinking water quality standards focus on a much narrower set of well-studied contaminants (e.g., certain pesticides, metals, disinfectant by-products and organics), and compliance with these standards remains very high although as we mentioned in a previous blog many of these are by definition very toxic substances just measured to low levels.

Current UK water protection frameworks covering environmental permits , the Water Resources Act , storm overflow reporting, and Drinking Water Inspectorate standards primarily focus on older, regulated pollutants. This leaves gaps in monitoring and enforcement, particularly for persistent or newly recognized contaminants. Rising storm overflows, increasing sewage spills, and widespread chemicals like PFAS threaten ecosystems and human health alike.

Harmful algal blooms, low-oxygen fish kills, bioaccumulation of persistent chemicals, and restrictions on shellfish harvesting demonstrate the ecological impacts , while recreational exposure and long-term health risks underline the public health challenge.

Together, these trends show that UK waters face mounting pressures from a growing cocktail of contaminants underscoring the urgent need for enhanced monitoring, treatment upgrades, and stronger regulatory frameworks.

Wastewater is increasingly recognised as a major driver of emerging contamination in UK rivers and groundwater, introducing a wide range of previously undetected or poorly regulated organic micropollutants into the water cycle.

Past issues such as metaldehyde contamination highlight how risks can go undetected until treatment failure occurs. Together, these gaps mean wastewater is acting as a continuous, diffuse source of chemical pollution, challenging existing regulations and increasing pressure on drinking water supplies as contaminants move slowly but persistently through the UK water environment.

Call thewaterdr for a free consultation about how you might improve your home or office setup.

About the Author

Nick Smith | Founder | The Water Dr. & Cellthyhomes

Nick has dedicated years to studying building biology, healthy living environments, and the impact of environmental toxins on inflammation.

Whilst regulations for UK drinking water are slow to adapt, & influenced by conflicts of interest, Nick conduct comprehensive research on global regulations & scientific literature to offer water filtration solutions that provide clean drinking water free from all harmful contaminants.